This is a short report about the Spanish currency during the 19th century. When the century began, the reales de vellón were the unit of account, that is, the normal currency used in official documents, like budgets or the tax collection reports. One real de vellón was equivalent to 34 maravedís, made of copper. But actually people used different coins and even different monetary systems in the country. For example, in the territories of the former Crown of Aragón they continued to use libras, sueldos and dineros. Monetary circulation was reduced and coins were more appreciated for the quantity of precious metals they contained (mainly silver). That's why people also accepted coins from other countries without much problem.

Silver real

Source: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_espa%C3%B1ol

Ferdinand VII's maravedí

Source: http://www.catalogodemonedas.es/?q=catalogo/monedas/25/2/241&MonedasPorPagina=100

The coins people commonly used were the multiples and divisions of the reales de vellón:

- the duro, also called peso, peso fuerte, real de a ocho or piastra, was worth 20 reales de vellón. These coins were so widespread that they have been found even in China. They probably arrived there from the Philippines. The $ symbol, that everybody associates now with the dollars, was in fact the logo of the duro and it represented the two Hercules columns with the motto Plus Ultra ( the great beyond) around them. When the USA chose this symbol for their currency, they were trying to link their money with the prestige of the Spanish silver coins.

Duro with Ferdinand VII's efigy

Source: http://blognumismatico.com/2011/12/14/los-retratos-de-fernando-vii-en-los-8-reales/

- As the duros value was very high for everyday transactions, smaller copper coins (calderilla) were minted: they were worth 1, 2, 4 and 8 maravedís. The ones worth 4 maravedís were called cuartos and the ones worth 8 were called ochavos or chavos.

The division of the reales into 34 maravedís complicated the everyday use. This was the reason for the monetary reforms made between 1848 and 1864:

- the real was adapted to the decimal system and divided into décimas and centésimas, eliminating the equivalence in maravedís, but this wasn't succesful.

- in 1864 the escudo, a new monetary unit, was created, equivalent to 10 reales and fractional copper coins were minted: 10 copper cents were worth 1 real

The division of the reales into 34 maravedís complicated the everyday use. This was the reason for the monetary reforms made between 1848 and 1864:

- the real was adapted to the decimal system and divided into décimas and centésimas, eliminating the equivalence in maravedís, but this wasn't succesful.

- in 1864 the escudo, a new monetary unit, was created, equivalent to 10 reales and fractional copper coins were minted: 10 copper cents were worth 1 real

However, the most important reform took place during the Democratic Sexenio. Minister Laureano Figuerola was responsible for the creation of a new coin, the peseta, and the definitive introduction of the decimal system.

- the peseta became equivalent to 4 reales (835 thousanths of silver=20 carats)

- the duro became equivalent to 5 pesetas (900 thousanths of silver=21.5 carats)

- the 10 cent copper coin became equivalent to 8 maravedís

Source:http://heraldicaculturanmefagf.blogspot.com.es/2014/06/131-caricaturas-de-la-revista-la-flaca.html

This cartoon from La Flaca qualifies Laureano Figuerola, minister of Finances, as Un duro, a play on words with the double meaning of the word duro (tough and the name of the coin). He is persecuted by the public opinion for the poll tax (capitación) he introduced.

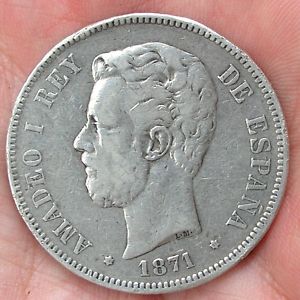

The name peseta came from a coin that had existed before in Catalonia during the Peninsular War and also in America, which was worth 4 reales, very similar to the French franc. Its equivalence facilitated the transition from the previous monetary system to the new one:

- the peseta became equivalent to 4 reales (835 thousanths of silver=20 carats)

- the duro became equivalent to 5 pesetas (900 thousanths of silver=21.5 carats)

Amadeus I's duro

Other smaller copper coins were minted, worth 1, 2 and 5 cents. As these new copper coins were created during the Sexenio, they didn't have the efigy of any monarch, but a lion with a shield on one side and a matron representing Spain on the other side. People didn't identify the lion and transformed it into a female dog (perra). The 5 and 10 cents copper coins were popularly known as perra chica and perra gorda.

Perra gorda

Source: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perra_gorda

Perra chica

Source: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perra_chica

The first peseta banknotes were printed in 1874, with the following values: 25, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 pesetas, but they were not used in normal transactions. They were destined to be used by banks and credit societies. The banknotes included the sentence: "The bank of Spain will pay to the bearer...". This meant that the banknotes were payment documents that could be exchanged for metallic money.

During the 2nd Republic other smaller banknotes were printed (5 and 10 pesetas), due to the devaluation of the peseta and in order to try to avoid the accumulation of silver duros. The silver duros were removed from circulation.

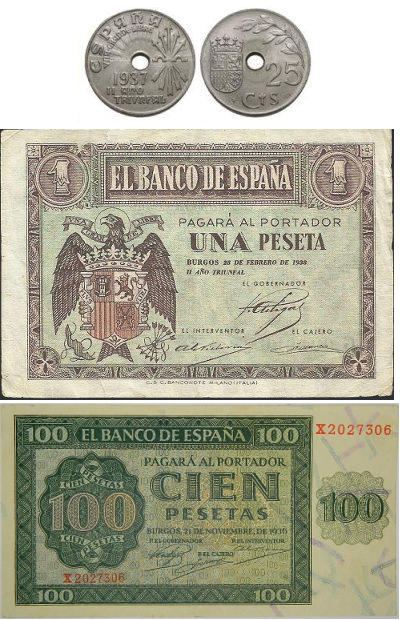

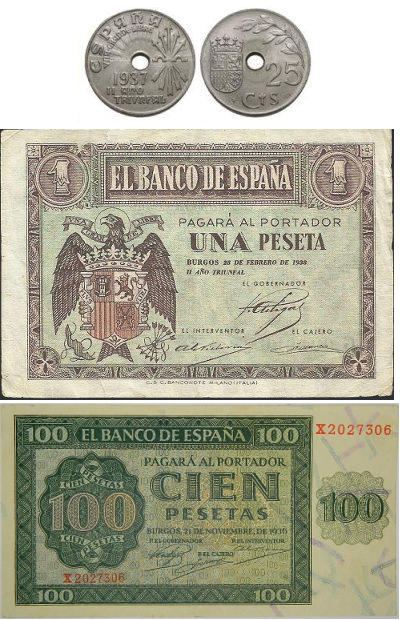

During the Civil War, the difficulties to buy metals obliged the government to print banknotes with very reduced value: 50 cents, 1 and 2 pesetas. Every contending side printed money and there were also numerous municipalities that printed banknotes.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The biggest peseta banknotes were created in 1976 (5,000 pesetas), 1980 (2,000 pesetas) and 1985 (10,000 pesetas).

In 1982 the Bank of Spain stopped printing 100 pesetas banknotes and the ones of inferior value, which were replaced for coins. In 1987 the 200 and 500 pesetas banknotes were also removed from circulation and replaced for coins. Finally, the peseta was replaced by the euros in 2002.

1874 banknote of 500 pesetas, dedicated to Goya

During the 2nd Republic other smaller banknotes were printed (5 and 10 pesetas), due to the devaluation of the peseta and in order to try to avoid the accumulation of silver duros. The silver duros were removed from circulation.

5 pesetas with an allegory of the Republic, printed in 1935

During the Civil War, the difficulties to buy metals obliged the government to print banknotes with very reduced value: 50 cents, 1 and 2 pesetas. Every contending side printed money and there were also numerous municipalities that printed banknotes.

Banknotes printed by the government of the Republic

Coins and banknote minted and printed by the rebels in Burgos

Source:

.jpg)

.jpg)

Money printed by the workers' communities of Híjar and Calanda (Teruel)

The biggest peseta banknotes were created in 1976 (5,000 pesetas), 1980 (2,000 pesetas) and 1985 (10,000 pesetas).

10,000 pesetas banknote, the biggest one printed

In Spanish, there are many common expressions related with these old coins, like tener muchos cuartos (referring to the cuartos), tener muchas perras (referring to the copper coins), which means "to have a lot of money", no valer un chavo (referring to the ochavos or chavos), which means being worthless, no tener una perra/ no tener una gorda (referring to the 10 cents copper coin), meaning "to be broke" or para ti la perra gorda, meaning "you win, we don't need to continue to argue".

Legal tender: moneda de curso legal

Bullion coin: moneda de ley (with a big amount of precious metal)

Carat: quilate

Thousandths: milésimas

Information extracted from Fontana, Josep, La época del liberalismo, Historia de España (dirigida por Josep Fontana y Ramón Villares), Volumen 6, Editorial Crítica/ Marcial Pons, Madrid, 2007

If you want to learn more about the monetary reforms from the arrival of the Bourbons to present day, here you have two more links:

https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/docs/446-2013-08-22-14%20legisla.pdf

- Del real al euro, by José Luis García Delgado:

https://books.google.es/books?id=laKz2B0knt8C&pg=PA31&lpg=PA31&dq=ley+de+reforma+monetaria+1848&source=bl&ots=WBt0WMR2Du&sig=chNfo1_MCBU_FOe8FzWzVLVEeRA&hl=es&sa=X&ei=HqrdVOGzF4LxUsmZg4AL&ved=0CFAQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=ley%20de%20reforma%20monetaria%201848&f=false

No comments:

Post a Comment